The Care Quality Commission (CQC) ‘is an executive, non-departmental public body of the Department of Health’ which ‘was established in 2009 to regulate and inspect health and social care services in England’ (Wikipedia, 2015).

The main role of the CQC is to ensure that hospitals, care homes, dental and GP practices and other health care providers are adhering to standards by which the safe, effective and high quality provision of services is met and/or improved. It was formed from three precursory organizations: the Healthcare Commission, the Commission for Social Care Inspection (CSCI) and the Mental Health Act Commission (MHAC). One of the CQC’s other roles is to protect the welfare of those whose rights are controlled under the Mental Health Act 1983.

Upholding fundamental standards of quality and care is central to the CQC achieving its goals. To this end, the CQC monitors, inspects and regulates dental services registered with it in a bid to encourage improvements and maintenance of standards expected by both the public and Government bodies. Part of an inspection includes listening to and acting on feedback from dental teams based upon their experiences as well as involving patients and gaining their views on services they have used. The CQC works in collaboration with the General Dental Council (GDC) and NHS England, forming a Tripartite Program Board, to take appropriate action if dental service providers are not reaching the standards set. Providers who fall below the standards will be challenged, with the poorest performers receiving the greatest attention and being required to take corrective action. Reporting on dental services is based on ‘fair and authoritative judgements’ and ‘supported by the best information and evidence’. Publishing of written reports is aimed at empowering the public to make informed choices regarding the dental care services they access.

What were the standards in 2010?

By April 2010, dental care providers were expected to have registered with the CQC and to have started to use its guidance for compliance, Essential standards of quality and safety, to ensure that they complied with the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2009 and the Care Quality Commission (Registration) Regulations 2009. Within the guidance, the CQC laid out 28 outcomes, each reflecting a particular regulation. Of these 28 regulations and outcomes, there were 16 that pertained unequivocally to the quality and safety of care and applied generically to all types of provider. The remaining 12 regulations applied in varying ways to different types of provider.

The 28 outcomes could be grouped into six main areas as laid out in Guidance about compliance: Summary of regulations, outcomes and judgement frameworks (March 2010):

1. Involvement and information

Outcome 1: Respecting and involving people who use services

Outcome 2: Consent to care and treatment

Outcome 3: Fees

2. Personalised care, treatment and support

Outcome 4: Care and welfare of people who use services

Outcome 5: Meeting nutritional needs

Outcome 6: Cooperating with other providers

3. Safeguarding and safety

Outcome 7: Safeguarding people who use services from abuse

Outcome 8: Cleanliness and infection control

Outcome 9: Management of medicines

Outcome 10: Safety and suitability of premises

Outcome 11: Safety, availability and suitability of equipment

4. Suitability of staffing

Outcome 12: Requirements relating to workers

Outcome 13: Staffing

Outcome 14: Supporting workers

5. Quality and management

Outcome 15: Statement of purpose

Outcome 16: Assessing and monitoring the quality of service provision

Outcome 17: Complaints

Outcome 18: Notification of death of a person who uses services

Outcome 19: Notification of death or unauthorised absence of a person who is detained or liable to be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983

Outcome 20: Notification of other incidents

Outcome 21: Records

6. Suitability of management

Outcome 22: Requirements where the service provider is an individual or partnership

Outcome 23: Requirement where the service provider is a body other than a partnership

Outcome 24: Requirements relating to registered managers

Outcome 25: Registered person: training

Outcome 26: Financial position

Outcome 27: Notifications – notice of absence

Outcome 28: Notifications – notice of change

These outcomes shaped amendments to the law recommended by Sir Robert Francis following his enquiry into poor care and high mortality rates at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. Adherence to these essential standards was intended to reassure patients that care providers would act with high ethics, with morality and within the law. Patients could expect to be treated with dignity and respect and receive dental care tailored to their requirements in a safe and compassionate environment.

Why did CQC standards change in 2015?

The CQC has acknowledged failings within its systems that led to conflict between providers and the CQC. Lack of clarity regarding which requirements were essential as opposed to desirable caused confusion and often hindered the implementation of good standards of dental care. Working out exactly what was required by the CQC resulted in precious time being inadvertently directed away from patient care and focused on computing which CQC requirements were a priority in practice.

In addition to this, Professor Steve Field, Chief Inspector of Primary Medical Services, stated: “We recognise the existing work of other regulatory and oversight bodies, and that the dental sector presents lower risk to patients’ safety. We have therefore started to design our new inspection and monitoring approach on a less frequent model of inspection. This statement sets out our early thinking on how we will do this and how we will work with our partners”. (A Fresh Start for the Regulation and Inspection of Primary Care Dental Services (August 2014) p.4).

This statement reflected a rethinking of the CQC’s strategy during their robust consultation period on proposed changes to be made. Historically, inspections had shown dental services to present a much lesser risk to patients’ safety than other care sectors. Therefore, a decision was taken to inspect 10% of dental practices on a ‘risk and random inspection’ basis as well as those organizations where there is cause for concern. The new strategy, Raising Standards, Putting People First: Our Strategy for 2013 to 2016, marked a new era for inspections and regulation and set out a clear purpose for CQC.

How has the inspection process changed?

The diagram below shows the operational model by which the new strategy works. This model is generic to all care services. However, dental care services will not be rated for the time being.

A New Start (2013) p.7.

The model displays four key functions:

1. Registration – The way in which providers apply for CQC registration has been reinforced, particularly with regard to how applications are assessed. In order to be registered, providers must demonstrate that they are able to meet the requirements displayed in the regulations. This incorporates two new regulations - Regulation 20: Duty of candour, and Regulation 5: Fit and proper persons: directors. The intention of Regulation 20 is to ensure transparency and openness with service users. Providers need to meet certain obligations if something goes wrong with treatment and care; namely robust and truthful communication about the incident, appropriate support and an apology. Regulation 5 is intended to make sure that anyone with director-level responsibility for meeting fundamental standards is fit and proper to undertake this essential function. Once registered, a provider is legally bound to meet all the regulations.

2. Inspections - Inspections will be carried out by ‘experts’, who will collate data, evidence and information to ‘intelligently’ assess and monitor services. Feedback from staff and patients will allow informed judgements to be made and action to be taken to make improvements. Those who are delivering poor care will be held accountable for it.

The essence of the new approach is patient-centred, with providers required to deliver safe, effective, compassionate and high-quality care. The following questions about providers will be asked during inspections:

• Are they safe?

• Are they effective?

• Are they caring?

• Are they responsive to people’s needs?

• Are they well-led?

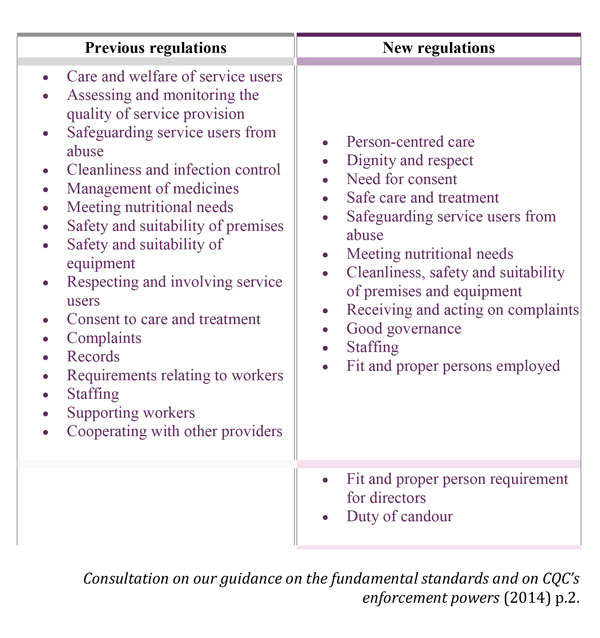

Inspections are now consistent and focused by using ‘Key lines of enquiry’ (KLOEs). KLOEs are sector-specific and designed to help inspectors judge the quality of care against the five central questions above. Inspections assess whether the prerequisites presented in the regulations are also met. There are now 11 new regulations that set out the fundamental standards of quality and safety in dentistry and supersede the previous 16 regulations. These new regulations are designed to be clearer assertions of the standards below which care should never falter.

A summary of the changes in regulation is shown in the diagram below:

3. Enforcement – Action will be taken if an inspection identifies concerns and will be proportionate to the severity and impact that the issues pose to the patients that use the service. If fundamental standards are breached, the CQC has power of enforcement, issued by the Health and Social Care Act, 2008, to ‘improve health and adult social care services and protect the health, safety and welfare of people who use them’ Care Quality Commission enforcement policy (February 2015).

4. Independent voice – The CQC will use reports, publications, articles and events to communicate their findings on behalf of service users.

What do dental nurses need to know?

Dental nurses need to be knowledgeable about and mindful of what the inspection teams will be looking for. The majority of inspections are announced, with a notice period of around two weeks. The exception is where the inspection is a ‘focused’ inspection in response to a concern or the identification of sub-standard practices during a previous visit. In this case, inspections can be unannounced. In busy dental practices, preparation time for inspections can be minimal so it is vital that fundamental standards are maintained at all times.

Recent CQC visits have focused on many key areas, including the following:

• Equality, diversity and human rights – The UK has become multi-cultural at a rapid pace and the CQC has specific concerns around communication and cultural differences, particularly with regard to informed consent. In addition to this, some groups within society, including disabled people and homeless people, have difficulty accessing primary dental care for both physical and resource-driven reasons. Inspectors are assessing how dental practices and individual staff are treating vulnerable adults and safeguarding their care based on the principles of ‘fairness, respect, equality, dignity, autonomy, right to life and rights for staff’. These principles are linked to the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Equality Act 2010.

• The Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA) – Within dental practices, inspectors are looking at whether the MCA is being used as a framework against which to treat people aged 16 and over who lack mental capacity to make decisions at the time. The aim is to ensure that people’s human rights are being safeguarded, particularly with regard to a person’s capacity to consent to, or refuse, proposed treatment or dental care. In the unlikely event that restraint is necessary and used to administer dental treatment, the CQC is looking for evidence that it is being used necessarily, appropriately and proportionately, in the best interests of the patient and in compliance with the MCA.

• Concerns, complaints and whistleblowing – CQC inspectors will be looking for evidence of how dental practices manage and respond to concerns and complaints made by those using their services. This will include discussing these issues with individual staff members and looking at complaints and whistleblowing policies and complaint handling files as well as speaking with patients. NHS Area Teams may also be asked about concerns, complaints and whistleblowing information that they retain.

• Disposal of mercury waste – Amalgam waste is classed as hazardous waste and as such should not be disposed of into the main sewerage system. Dental practices are required to install amalgam separators that meet British Standard ‘Dental Equipment – Amalgam Separators’ (BS ISO EN 11143:2000) standards and dispose of amalgam waste in accordance with The Hazardous Waste Regulations 2005. Inspectors will be looking for physical evidence of ‘safe’ disposal of hazardous waste as well as practice policies and procedures, consignments notes and staff training and inductions.

• Radiography and X-rays – Dental practices and staff must comply with Ionising Radiations Regulations 1999 (IRR99) and Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2000 (IR(ME)R 2000) in relation to patient protection. These regulations are enforced by CQC. Inspectors will be looking for evidence of a designated Radiation Protection Adviser and Radiation Protection Supervisor, a copy of the Local Rules specific to each unit, a practice risk assessment, training for staff and practice policies pertaining to restriction of exposure, maintenance, servicing of engineering controls, contingency plans and controlled areas.

• Medical emergencies – CQC inspectors are looking for evidence that dental practices are following guidance laid out for medical emergencies and staff training updates published by the Resuscitation Council (UK). This includes physical evidence that the practice and staff are prepared to deal with a medical emergency. For example, the necessary drugs and equipment needed to deal with any given medical emergency situation should be on site and located in a central position accessible to all staff. Inspectors are assessing whether quality assurance processes, such as checking drug and equipment expiry dates weekly, are in place.

Conclusion

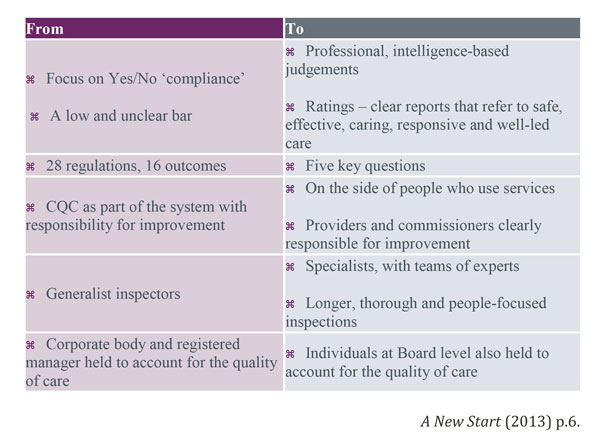

The regulation and monitoring of dental services is a vast topic area and it would be advisable for those reading this article to study the documents included in the bibliography and reference list. This article has served to highlight the differences between the old and new CQC regulations and inspection methods. These are summarised in the diagram below.

Author: N Rowland BSc, Dip Man

Bibliography and references

1. www.cqc.org.uk

2. Quick Guide to the Essential Standards, Care Quality Commission, 2010.

3. Guidance about compliance: Summary of regulations, outcomes and judgement frameworks, Care Quality Commission, March 2010.

4. A Fresh Start for the Regulation and Inspection of Primary Care Dental Services, Care Quality Commission, August 2014.

5. Raising Standards, Putting People First: Our Strategy for 2013 to 2016, Care Quality Commission, May 2013.

6. A New Start, Care Quality Commission, June 2013.

7. Consultation on our guidance on the fundamental standards and on CQC’s enforcement powers: A quick guide, Care Quality Commission, July 2014.

8. Care Quality Commission enforcement policy, Care Quality Commission, February 2015.

9. How CQC Regulates Primary Care Dental Services: Provider Handbook, Care Quality Commission, March 2015.

10. http://www.kldc.org.uk/information/cqc-inspection-questions-asked

11. www.docplayer.net